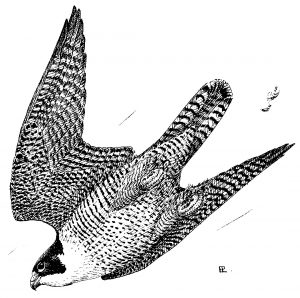

Photo: Peregrine Falcon nestlings prepare to take their first flight in downtown Reading last month. Photo by Bill Uhrich

It’s nearing dusk.

The streets in center-city Reading are quiet, as the daytime bustle – diminished by the coronavirus restrictions on restaurants and employers – is reduced to a few pedestrians strolling Penn Square.

But there’s action overhead.

Now that two surviving Reading Peregrine Falcon young have successfully fledged, they’ve been working their wings in the low sunlight and the early evening breezes that swirl around the top of the Berks County Courthouse.

It’s also the last feeding time before dark, but the young falcons, although gaining proficiency on the wing, still lack the hunting skills to capture their own prey.

So they sit at their favorite meal spots – the edges of the Callowhill Center at Fifth and Penn, the upper reaches of the Madison Building in the 400 block of Washington Street or the ledges around the steeple at Trinity Lutheran Church in the 500 block of Washington Street.

They sit and beg, their shrill cries reverberating throughout the brick and stone canyons of the downtown, as they wait for their parent birds to drop a prey item to them from out of the sky.

The Peregrine is the fastest animal on Earth, capable of reaching speeds of up to 200 miles an hour in a stoop as it zooms in on its prey.

And the city of Reading has been blessed for 14 nesting seasons with the presence of the magnificent Peregrine Falcon, the bird of kings, in the downtown.

***

The success story of the Peregrine Falcon in Berks County is one that has its roots in the hawk slaughter along the Kittatinny Ridge a century ago until the formation of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in 1934 put an end to the practice in northern Berks.

Pennsylvania state ornithologist George M. Sutton noted at the time that two were shot there on Oct. 22, 1927.

An immature male was also shot there on Oct. 6,1929, and another male was taken there on Oct. 3, 1933. Both of these specimens are in the collection of the Reading Public Museum.

There also were positive developments for the success of the Peregrine.

The formation of Lake Ontelaunee in the late 1920s provided suitable habitat that attracted waterfowl, and consequently, the Peregrine Falcon, previously known as the Duck Hawk.

Ornithologist and Reading Public Museum director Earl L. Poole visited the newly flooded lake on March 31, 1929, and wrote in his journal:

“…two Black Ducks detached themselves from a flying flock and started down toward the water. Suddenly as I had my glasses on them, a fine male Duck Hawk appeared from nowhere and swooped. I saw him stretch out one leg, turn over, and make a grab for one of the ducks, which dodged, and both hit the water in a hurry. The hawk started to soar in short circles, getting higher and higher. All this time as I watched it a flock of hundred of Pipits was continuously passing over, looking through the glasses like black stars against the sky.”

Lake Ontelaunee and Hawk Mountain in the early and middle 20th century were the two most reliable places to find Peregrine Falcons in Berks.

Peregrines had nested in the state on cliffs along rivers and streams, but no nestings had occurred in Berks.

But following World War II, the Peregrines in Pennsylvania faced a new threat – the accumulation of persistent pesticides like DDT from their prey resulted in eggshell thinning. The weight of the brooding female would crush the eggs.

Although the Peregrine was never a common migrant at Hawk Mountain, the pre-War single-day high count was 11 on Oct. 7, 1937, with a season high of 45 in 1941.

According to the Pennsylvania Game Commission, the last nesting of Peregrine Falcons in the state occurred in 1959, and shortly thereafter, the bird nearly disappeared in the East.

The Peregrine counts at Hawk Mountain reached their lows in the early 1970s with six birds recorded in 1972 and 1975.

The Peregrine was placed on the federal Endangered Species List in 1972.

***

Reading played a role in the Peregrine’s reintroduction and comeback in the East during the early 1990s.

The Pennsylvania Game Commission released Peregrines in Allentown, Harrisburg, Williamsport and Reading as part of a “hacking” project to bring the bird back to the East. Hacking is the process whereby immature birds are gradually released into the wild.

As part of the Peregrine Falcon reintroduction program, the game commission placed nestling Peregrine Falcons at several sites in Reading from 1993 to 1995. Todd Morgan of Birdsboro oversaw the project.

The nestlings were usually taken from nests on bridges in Philadelphia, where fledging success was low due to the danger of drowning in the Schuylkill River.

In 1993, a male and female Peregrine were “hacked” from the top of the Berks County Services Center at Reed and Court streets. The male soon disappeared, but the female survived the summer. She was found dead, however, in Maine in 1995.

In 1994, three falcons, two males and one female, were hacked from atop the Eisenhower Apartments at Ninth and Franklin streets.

The female from that group made it to Toronto, Ontario, where she was found nesting the following year. Canadian Fish and Wildlife officials documented two young, three weeks old, on June 14, 1995, the first nesting activity of a Peregrine Falcon hacked in the state-wide program.

The female had mated with a male hatched in Akron, Ohio, and according to the Canadian Peregrine Foundation, represented the first Peregrine Falcon nesting in southern Ontario in 30 years.

The pair successfully nested each year until 2002, when both were killed defending their brood of five young from other Peregrines. The five young were rescued, raised and released.

The pair had successfully raised a total of 29 young.

In 1995, five falcons, three of which were from a nest on the Walt Whitman Bridge in Philadelphia, were hacked from atop the Eisenhower Apartments.

There were no later sightings or recoveries of those birds.

Because of the success of the reintroduction efforts throughout the East, the Peregrine Falcon was removed from the federal Endangered Species List in 1999 and from the state list in 2019.

***

Counts at Hawk Mountain reflect the success of the growing Peregrine population with a season high count of 88 in 2014.

Last year, 56 Peregrines were counted from the North Lookout with a daily high of 11 on Oct. 4.

***

In late winter of 2007, a male and female Peregrine first engaged in mating flights over Reading. The adult male falcon had been banded, and observers were able to determine from the band that it was one that hatched atop the Rachel Carson Building in downtown Harrisburg in 2005. The female was unbanded.

The falcons picked the Madison Building as their nest site, raising two young for the first Berks County nesting records.

The young were banded, but one fledgling disappeared soon afterward, and the other was found dead on the roof of unknown causes.

The next year, the falcon pair moved their nest site to a building in center city, where they have successfully raised young every year since.

In 2015, the original adult female was replaced by a falcon that had fledged in 2011 from the Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge between York and Lancaster counties, and she and the original male are still the dominant Peregrine pair in the downtown.

***

The two young Reading falcons look skyward as they beg with harsh cries for their supper.

The female swoops in with prey, and the young devour it.

Soon, they will be hunting on their own, and observers can watch their progress from the streets below.

The Latin name for the Peregrine is Falco peregrinus, which means wanderer.

By late July, the adults will push the young out of their territory for them to embark on their own wanderings throughout the North American continent.

The adults will remain behind for a few months, occasionally returning throughout the winter to perch on the cross of Christ Episcopal Church at Fifth and Court streets or sit atop the courthouse to stake their claim on their territory from any other wandering Peregrines.

And with hope, the mating and nesting cycle will begin anew for the 15th year.

***

The following is a round-up by year of the nesting success at the Reading site, according to Art McMorris, Peregrine Falcon specialist for the Pennsylvania Game Commission:

2007:

Two young, both banded; one dead before fledging, cause unknown;

2008:

Three young, not banded; falcons moved their nest site and site not found until close to fledging. All three fledged.

2009:

Four young; all banded. All fledged.

2010:

Four young; all banded. Two died of trichomoniasis after fledging/before dispersing; one found dead in nest, cause unknown, but trichomoniasis likely; one hit by a car near nest soon after fledging, rehabbed and released.

2011:

Two young, both banded, both fledged. One found near nest with fractured ulna, apparent collisions with building or vehicle; rehabbed but not releasable, transferred to Carbon County Environmental Center and used as an education bird.

2012:

Three young, all banded, all fledged; one found dead after dispersal on Aug. 28, 2012, at Philadelphia international Airport after a collision with a plane. One observed at “Hawk HIll’ raptor banding station in Ontario on north shore of Lake Erie Sept. 13, 2012, alive and free, 320 miles from nest site.

2013:

Four young, all banded. All diagnosed with early-stage trichomoniasis at or soon after time of banding; all treated and returned to nest. All fledged successfully. One found dead after dispersal in Massachusetts, Aug. 1, 2013. One found alive and free after dispersal, Aug. 9, 2013, in Lyndhurst, N.J., 100 miles from nest site.

2014:

Four young, all banded. One died at the nest site of unknown cause.

2015:

Four young, all banded. Female B13, “Red,” was photographed in October on the beach at Holgate, N.J. exhibiting dominant behavior. This same female was observed, alive and free, in the vicinity of Barnegat, NJ, on May 5, 2016, approximately 20 miles from Holgate. It was seen feasting on shorebirds and dominating the other birds in general.

Another female from the 2015 Reading nest was observed alive and free on May 24, 2018, and again on March 24, 2019, on Parsonage Island in Long Island Sound, NY.

2016:

Four eggs, four nestlings banded and fledged.

No evidence of trichomoniasis was observed by visual inspection when the nestlings were banded on May 25, but all four were given a prophylactic dose of 10 mg. carnidazole. No rescues or injuries post-fledging.

2017:

Four eggs, four nestlings banded and fledged.

No evidence of trichomoniasis was observed by visual inspection when the nestlings were banded on May 22, but all four were given a prophylactic dose of 10 mg. carnidazole. Oral swabs were taken for trich analysis at the time of banding; all four were negative. No rescues or injuries post-fledging.

2018:

Four eggs, four nestlings banded and fledged.

When banded on May 18, one nestling had signs of moderately-advanced trichomonas infection, and was taken to rehab for a one-week course of treatment, and then returned to the nest when the disease had cleared on May 25. The other three nestlings were treated prophylactically with 10 mg. carnidazole at the time of banding and returned to the nest. All four fledged at the appropriate age during the first week of June. No rescues or injuries post-fledging.

2019:

Four eggs, four nestlings banded and fledged.

When banded on May 20, three nestlings had signs of trichomonas infection, and were taken to rehab for treatment. They responded well to treatment, and were returned to the nest three days later, on May 23. The fourth nestling was treated prophylactically with 10 mg. carnidazole at the time of banding and returned to the nest. All four fledged at the appropriate age in mid-June.

Two fledglings were subsequently rescued:

One was found grounded on June 13, taken to rehab, held there for four days to put on weight, and then released back at the nest site on June 17.

The other was rescued after it had collided with a building and was taken to rehab in guarded condition, bleeding from the glottis. It recovered well in rehab and was released back at the nest site five days later, on June 28.

At the time of release, both rescued fledglings were fitted with Motus nanotags so their post-dispersal movements could be tracked. Tracking data is currently being analyzed.

Both fledglings that were rescued, rehabbed and released were seen flying well after release.

2020:

The season is still in progress, so data are incomplete. But to date:

Four eggs, three nestlings and one unhatched egg (it is not at all unusual for one egg in a clutch not to hatch). All three nestlings have fledged at the appropriate age. No rescues or injuries to date. In order to maintain social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, the nest was not visited for banding.

BCTV is collaborating with local journalists to bring you the stories of our community during the COVID-19 pandemic. This media partnership is made possible in part by the support of The Wyomissing Foundation.